“We shall not cease from exploration/And the end of all our exploring/Will be to arrive where we started/And know the place for the first time.”

These lines from T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets speak to the unexpected resonance, the deepest of chords I felt when returning from a week in Alaska on June 23rd. I had journeyed to Alaska 52 years ago having just graduated from college, seeking adventure, testing a personal relationship and wanting to kick away the traces. In Eagle Village five decades ago I found a muscular church, a face of the church I’d never seen, a church that engaged the community on all levels, a faith that got dirty. Inspired by some amazing (and humorous) Alaskan priests, I decided at the end of the summer not to honor my commitment to teach in Newtown, MA, that fall but to attend divinity school. At that point my fledgling career took a major shunt. For me that six weeks (or was it eight?) proved seminal.

These lines from T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets speak to the unexpected resonance, the deepest of chords I felt when returning from a week in Alaska on June 23rd. I had journeyed to Alaska 52 years ago having just graduated from college, seeking adventure, testing a personal relationship and wanting to kick away the traces. In Eagle Village five decades ago I found a muscular church, a face of the church I’d never seen, a church that engaged the community on all levels, a faith that got dirty. Inspired by some amazing (and humorous) Alaskan priests, I decided at the end of the summer not to honor my commitment to teach in Newtown, MA, that fall but to attend divinity school. At that point my fledgling career took a major shunt. For me that six weeks (or was it eight?) proved seminal.

Over the years my mind told me that Eagle had propelled me to divinity school – first in Berkeley, California, to The Church Divinity School of the Pacific, and then for the last two years to the Episcopal Divinity School in Cambridge, MA, and then into civil rights. Martin Luther King picked up and focused my passion for service, a passion that began in Eagle.

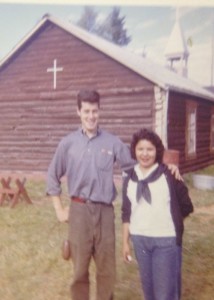

But my historical memory didn’t serve me well. It got the divinity school part right, but not the other – the service part. While in Eagle, Ethel Paul, then 19 and wise beyond her years, the de facto anchor of the village whose adults were affected by alcohol much of the time, her brother Tony Paul at 17, a golden boy, a star at everything he tried and sexy, impish Bertha Paul and I “organized” a floating youth camp interspersed with help for the adults. I started a choir and a ball team; we hiked, fished, panned for gold, and as Ethel reminded me, we played a lot of Monopoly. According to Ethel, the four of us were together “all the time,” either at the parish house – yes I conducted services and “played” the pump organ – or three miles down the road in the village where we built a teen center (read shack). Call us friends, staff, colleagues, fellow pilgrims or a family (no physical romance as I was engaged to be married), we were together a great deal, often with lots of kids trailing around us.

“What will I do,?” I asked Bill Gordon, Alaska’s legendary bishop when he let me off on the meadow near the church in 1962. “You’ll figure it out,” he said. “Just make sure to keep the grass scythed so I can land the plane.” With Ethel and her siblings, we may not have “figured it out,” but we certainly had fun trying.

Here’s how I got it wrong: civil rights was but one manifestation of my slowly emerging, then unarticulated commitment, which became lifelong, a commitment to the well being of children, youth and their families and the communities in which they lived. Did I recognize it then? At the time, absolutely not. Seeing the church in action and a trio of kids trying to stitch together, to reconnect a fraying community were the gifts I received from Eagle, Alaska. Eagle also taught me about the importance of jobs: when the salmon began to run, the villagers stopped drinking. They built an amazingly complicated “fish wheel” made up of bent saplings and various parts of a caribou, a huge “wheel” that, propelled by the strong Yukon current, combed the waters, lifted up the “combed” fish, which wound up sliding down a slanted 6-8 foot chute onto tables and into the waiting arms of villagers with knives. MIT students would have marveled. Drying racks spanned the length of the village.

Now, 52 years later, I walked across the Natives’ Community Center floor last Tuesday on June 17th, Ethel walked slowly toward me. Was this Ethel? Was this really happening? Was it real? I cupped her face in my hands. We hugged for several minutes, shedding tears of disbelief and joy. Later Bertha, who still lived in the village took both my hands and said, “Welcome home, Jack.” If “home” is where it all starts, Bertha nailed it. I learned later that Tony had died an alcohol-related death. Within minutes Ethel and I were pouring over pictures of kids and grandkids.

Now, 52 years later, I walked across the Natives’ Community Center floor last Tuesday on June 17th, Ethel walked slowly toward me. Was this Ethel? Was this really happening? Was it real? I cupped her face in my hands. We hugged for several minutes, shedding tears of disbelief and joy. Later Bertha, who still lived in the village took both my hands and said, “Welcome home, Jack.” If “home” is where it all starts, Bertha nailed it. I learned later that Tony had died an alcohol-related death. Within minutes Ethel and I were pouring over pictures of kids and grandkids.

I recall the Eagle of 1962 as being full of kids. Perhaps not. But today there are only two out of a total of 26 people. Seven miles up the road – it was once three, and we walked it, but the flood of 2009 wiped out the “old village” –lies “Eagle Town” where roughly 110 people live. In 1905 during the Gold Rush, there were about 400 inhabitants. The town and village abut the

I recall the Eagle of 1962 as being full of kids. Perhaps not. But today there are only two out of a total of 26 people. Seven miles up the road – it was once three, and we walked it, but the flood of 2009 wiped out the “old village” –lies “Eagle Town” where roughly 110 people live. In 1905 during the Gold Rush, there were about 400 inhabitants. The town and village abut the  mighty Yukon River, located almost due east of Fairbanks and four miles from Canada’s Northwest Territories. Upon birth, whether in the U.S. or Canada, the Athabaskan – a Native American tribe spanning much of central Alaska and Canada’s Yukon Territory – are born with dual citizenship. The scenery is breathtaking.

mighty Yukon River, located almost due east of Fairbanks and four miles from Canada’s Northwest Territories. Upon birth, whether in the U.S. or Canada, the Athabaskan – a Native American tribe spanning much of central Alaska and Canada’s Yukon Territory – are born with dual citizenship. The scenery is breathtaking.

Ethel and a few of the older villagers still hold onto a vision of the village “coming back,” a place that attracts talent and commitment, rather than witnessing its flight to Anchorage or Fairbanks.

When I decided to go, I discovered that Ethel was still there (what an emotional telephone conversation that was!). I told her that I had planned to visit Eagle the last week in June, but she informed me that a Habitat group of nine from Texas was coming up to build the village church that had been destroyed by fire. So I joined the group, a group led by two bishops, one from Alaska, one from Dallas – again, faith in action.

When I decided to go, I discovered that Ethel was still there (what an emotional telephone conversation that was!). I told her that I had planned to visit Eagle the last week in June, but she informed me that a Habitat group of nine from Texas was coming up to build the village church that had been destroyed by fire. So I joined the group, a group led by two bishops, one from Alaska, one from Dallas – again, faith in action.

During my brief week, we – including the bishops – leveled (the footings had not been poured, so we had to build 8 x 8 piers), notched, lugged, caulked, nailed, put in joists, braces, chicken wire to hold the insulation and then, finally, the floor. At last we were able to start on the log walls. The energy of the two bishops, one in purple, and the other standing on his left never flagged.

During my brief week, we – including the bishops – leveled (the footings had not been poured, so we had to build 8 x 8 piers), notched, lugged, caulked, nailed, put in joists, braces, chicken wire to hold the insulation and then, finally, the floor. At last we were able to start on the log walls. The energy of the two bishops, one in purple, and the other standing on his left never flagged.

And so for a week we got as far as we could with the material at hand. On Sunday, my last day, we celebrated mass/communion on the church’s now-level, insulated plywood floor with log walls about waist high.

And so for a week we got as far as we could with the material at hand. On Sunday, my last day, we celebrated mass/communion on the church’s now-level, insulated plywood floor with log walls about waist high.

The Texas crew stayed one more day, able to finish the “12-log” wall. Still no girders, ridge pole or roof. The tribal council meets in August to figure out how to finish the job, but Ethel harbors no concerns at all: “Jack, for last week to have happened, anything can happen. The church will be rebuilt.”

During that week, I met a man working for FEMA who was under contract to restore a historical building in Eagle Town. He needed plywood, and the nearest Home Depot is a nine hour drive or two hour plane ride. Thus bartering is alive and well. For the church floor, the storage shed held more than enough plywood. We had extra. “If I get you plywood, what will you do for the village?” I asked Don. “I’ll build an ‘old time’ frame for the bell if you can find it and send me a picture.” With approval of the village, I got an overwhelmed Don two large pieces of plywood. He’ll build the bell’s frame from the picture I sent him.

I still don’t quite know what to make of my week in Eagle, except perhaps this: hope really does matter – hope, will and focus. And this: for me the trip this year to Eagle, which started as an adventure to connect to a long ago past, wound up as an epiphany, a discovery of what got me started in the first place – for when I returned from Eagle the first time, half a century ago, I finished my divinity school degree and declined ordination, choosing rather youth and community development work in Boston. When I returned to Eagle, a long career of helping youth and communities now behind me, I went to a place and unwittingly touched my touchstone, knowing it for the first time…

If you have the opportunity, go back to that place where you started. Revel in it. Remind yourself how you got started, why you got started, who got you started. Go back, look around…and give thanks.

Tracy Colunga says

Tracy Colunga says

July 2, 2014 at 8:30 pmI read this and sat almost in tears at my desk. This article touch my soul as I remember back to South Bend, IN where it all started for me. Thanks for sharing Jack.

Tracy Colunga

City of Long Beach, CA